Everyone is talking about SPACs.

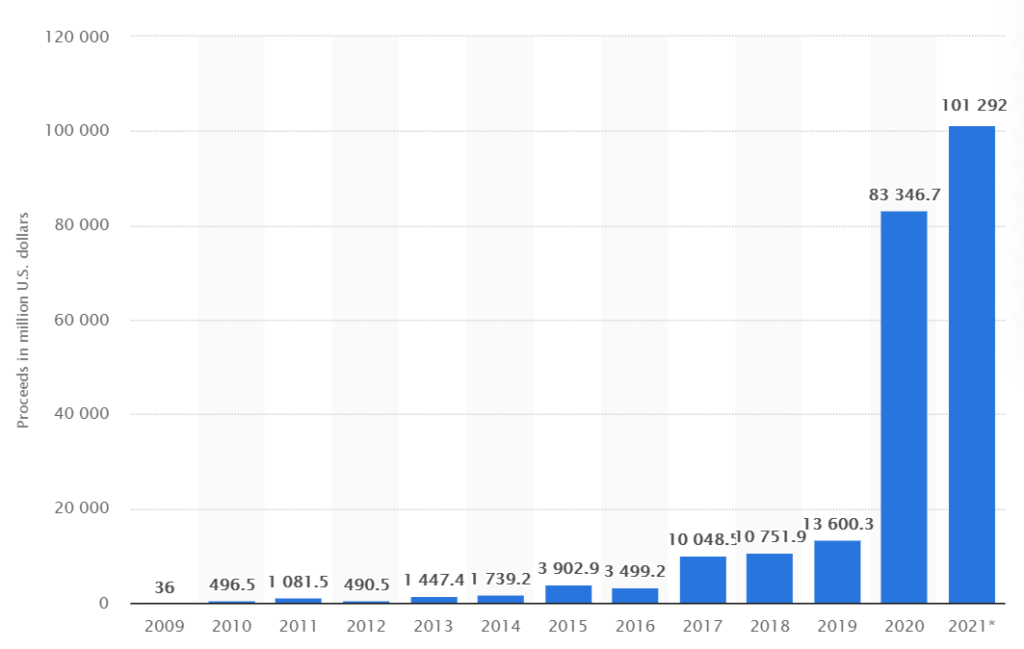

Indeed, SPACs have been raising money from investors quicker than ever in history. More funds have been raised through SPACs in 2020 than the past 10 years combined – in fact, almost twice as much! At the end of April 2021, SPACs had already raised a massive US$101.3 billion since the start of the year in the United States alone.

Things are only going to get wilder from here. On 13 April 2021, Singapore-based Grab Holdings Inc. announced the largest ever SPAC deal valued at US$39.6 billion and is expected to list on NASDAQ under the ticker symbol GRAB.

SPACs seem to be the next big thing in the investing world – or are they?

Proceeds of SPAC IPOs in the US from 2009 to April 2021. Source: Statista

How SPACs work

What then is a SPAC and how does it work?

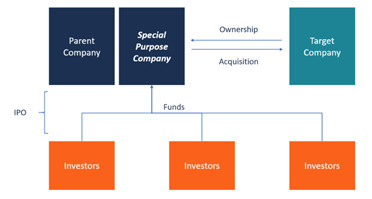

A Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC) differs from an ordinary company because it has no existing business operations. It offers no product or service of its own – it is essentially a shell company. A SPAC’s only purpose is to raise capital through an initial public offering (IPO) from institutional and retail investors, and the SPAC gets listed on a public stock exchange. Thus, the SPAC’s only assets are the capital raised in its own IPO.

Subsequently, a SPAC uses the capital raised to acquire an existing company – let’s call this Company X. The SPAC will generally have a specified duration (e.g. 2 years) to acquire a company, and it can complete this acquisition at any time during this period. When the specified acquisition period ends and the SPAC has not yet acquired a company, the SPAC is liquidated and must return the money back to investors.

This Company X, which the SPAC acquires, has existing business operations itself. After the merger between the SPAC and Company X (the “De-SPAC process”), the newly merged company will be listed on the stock exchange under a new ticker symbol, usually in the name of Company X.

Source: Corporate Finance Institute

Why would SPACs be an interesting alternative for private companies to achieve listing on a public stock exchange? There could be a myriad of possible reasons, including potentially selling for a higher price compared to a traditional IPO, the faster process of listing than the traditional IPO route, and less burdensome and costly regulatory requirements.

Who is involved in a SPAC transaction

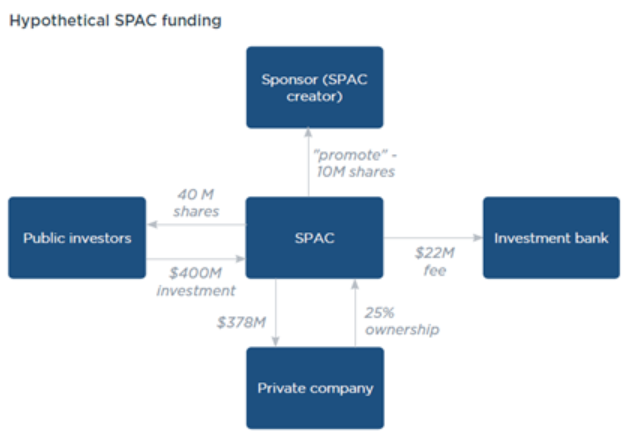

A SPAC transaction involves several main parties, namely the sponsor, the investors, the underwriter and the target company.

Sponsor

First, the sponsor creates the SPAC. Sponsors are typically investors or people with strong business expertise, and they inject some of their own capital (“sponsor capital”) into the SPAC pre-IPO. An example would be Bill Ackman, an American billionaire hedge fund manager, who sponsored his own SPAC Pershing Square Tontine Holdings (NYSE: PSTH).

In exchange, the sponsor receives a “promote” as compensation, which are shares equivalent to 25% of the SPAC’s IPO proceeds (which constitutes 20% of the total post-IPO equity of the merged company). This is also known as “founder’s shares”. For example, if the SPAC raises $40 million from the IPO, the sponsor receives shares equal to $10 million (25% of IPO proceeds). The sponsor’s shares ($10 million) thus constitutes 20% of the total post-IPO equity ($40 million + $10 million = $50 million).

Underwriter

The underwriter is usually an investment bank with industry experience and connections to institutional investors. It helps to look for prospective investors for the SPAC’s IPO. Post-IPO, the underwriter may be tasked to look for conflicts of interest, bring potential acquisition opportunities to the SPAC and assist with the acquisition process.

The underwriter receives a commission or fee, which is a small percentage of the SPAC proceeds.

Target company

The target company is the company being acquired by a SPAC. It is usually a privately held company and has its own business operations, unlike a SPAC. The target company sells a percentage of its shares to the SPAC in the acquisition, in exchange for cash proceeds.

Investors

Investors are those public investors (institutional or retail) who put capital into the SPAC through the IPO or private investors through a Private Investment in Public Equity (PIPE) transaction.

PIPE is a method for SPACs to raise additional capital from these private investors to acquire the target company. For example, the sponsors negotiate with the target company to have a post-merger valuation (of the eventually merged company) of $1 billion, and the pre-merger valuation of the target company is agreed to be at $500 million. Hence, a total of $500 million needs to be raised by the SPAC to reach this $1 billion valuation. If only $300 million was raised from the initial IPO, then an additional $200 million will be raised by the SPAC through a PIPE deal from private investors in exchange for shares in the SPAC.

Source: Morningstar

Notable deals

The most-talked about SPAC merger in recent times is the acquisition of Grab Holdings Inc. (“Grab”), a Southeast Asian superapp unicorn, by the SPAC Altimeter Growth Corp (NASDAQ: AGC). The Grab SPAC deal is valued at nearly US$40 billion i.e. the valuation of the combined company. This is the largest SPAC deal so far in the world.

Another notable SPAC deal is the US$1.5 billion merger between Virgin Galactic – Sir Richard Branson’s spaceflight company – and the SPAC Social Capital Hedosophia (“SCH”) by venture capitalist Chamath Palihapitiya. SCH took a 49% shareholding in Virgin Galactic at the time of the acquisition. The merged company now trades on the NYSE under the ticker symbol SPCE as Virgin Galactic Holdings Inc.

Sir Richard Branson and Chamath Palihapitiya. Source: Seeking Alpha

The way forward

In actual fact, SPACs are nothing new. They have already been around for some time, since the early 1990s. But recently SPACs have gained traction and popularity on the back of some high-profile SPAC transactions like Virgin Galactic, DraftKings and now Grab.

Today, high-growth technology companies are using the SPAC process to go public given the shorter timeframe as compared to undergoing traditional IPOs themselves. The global COVID-19 pandemic has also invariably caused such companies to search for alternative means to raise capital from the public easier and faster. Given the post-COVID market volatility, SPACs could become more appealing than traditional IPOs because the target company can negotiate its own fixed valuation with the sponsors in a SPAC acquisition. This gives a level of price certainty as compared to traditional IPOs where the company’s valuation is determined mostly by the market.

Times are changing, and we might just be seeing a comeback of the SPACs – or it could simply be a bubble waiting to burst.